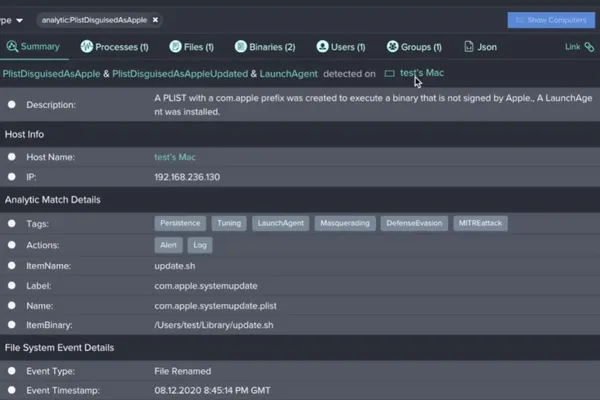

Like real-life incidents, this security incident response demo begins with an alert created from a system detection. In this scenario, Jamf Protect found a PlistDisguisedAsApple alert and it's time to dive in.

In any situation where the system detects a LaunchDaemon name with the prefix "com.apple" but the executable that is being prompted is not signed by Apple, this PlistDisguisedAsApple alert fires. As we can see in the SystemUpdater application in question, the plist name implies it is owned by Apple and should go on to execute a process signed by Apple but instead it goes on to execute an unsigned executable. This is suspect and requires further investigation.

File types and naming also come into play in this initial assessment of the generated alert. In Processes, you’re able to view additional information for greater context.

You can see no developer signed or claimed this app; it was signed "Ad Hoc". Although this approach to signing information can be used for testing, malware often behaves like this and it should be a concerning data point in your assessment. The file is named com.apple.systemupdate.plist, but is sitting in the user's Library directory, attempting to run at startup as a shell script, which is indicated by /Users/test/Library/update.sh — and is another red flag.

If an executable file is in a user's library directory, which is generally meant to store additional directories rather than executables, this indicates further suspect behavior. We can also determine that, because the application is sitting in /AppTransloction/, this is its first time running on the system.

Within Binaries, you are able to see even more details about what the executables that are connected to this suspect process, and we are able to confirm that the application is quarantined within the logged extended attributes (XAttrs): com.apple.quarantine. This tells us that this file was download to the device from the internet from a web browser, chat mechanism or other internet-based action. We again are notified that this application is not signed and, in this same view, we can see additional XAttrs information. This time, the XAttrs: com.apple.TextEncoding does not convey information that sways us one way or the other in this situation, but it is an insight that can provide additional information to shape other incident response scenarios.

The next step is to view the affected device the alert was detected on in the Users section. At this point in the investigation, we want to determine if the application was run as the root user, which would give an attacker full access to the system. In this demo case, the root user appears to be unaffected and we can continue with the information we have acquired so far. We know:

- SystemUpdater.app was downloaded from the internet

- SystemUpdater.app was not signed by a developer

- SystemUpdater.app wrote a persistence item named systemupdate.plist, which will launch a script named update.sh at startup

All of this information was collected from one single alert but, we still need more information. We need to know:

- Where the malware came from

- Its intended outcome or goal

We need to investigate further and ask, "were any additional alerts or logs created on the system around the same time?"

After digging into the user's Mac logs, we can see that a number of additional logs were created at the same time the suspicious file was downloaded onto the device.

In the detailed view of the logs, we see SafariWritesCustomUrlHandler with the value of "SystemUpdate" that was created at the time the application was downloaded. A CustomUrlHandler scheme is a way for one application to request another application be opened and, sometimes transfer data. It is not malicious in nature but it is a functionality that has been used in by malware in the past. In this case, the application’s CustomUrlHandler will be registered as soon as it's downloaded. The attacker can then redirect the user to the custom url scheme which will request the application to be opened pending a few user prompts.

At this point in the incident response process, Jamf Protect has been used to assess the alert and collect more information to aid you in your investigation. But for the next steps to remediate the security incident, it's time to harness the power of Jamf Pro.

When you are ready to collect the files and dive further into this incident:

- Log in to Jamf Pro

- Navigate to Settings

- Select Scripts

- And create a batch script to run what you have determined you need based on the input criteria

The information you requested in your script will be collected and pushed via the Jamf Pro API. Next, you will create a policy that is configured to run the next time the affected computer checks in with Jamf Pro.

Creating a policy that is configured to run the next time the affected computer checks in with Jamf Pro is the next step in this incident response. After this policy was configured and the computer checked in, the collection script delivered the user's Safari browser history and interesting insight into what occurred and the moment of the attack.

Attackers often buy domains and try to appear as a valid, recognizable site to the end user. But in this case, we can see an IP address was used without attempting to blend in with a domain. This is inherently suspicious and indicates additional investigation is needed.

The LSQuarantine Database on MacOS — a SQL light database stored on the user’s home directory and library preferences — provides a full record of what has been downloaded onto the system from various applications. And we can confirm that Safari downloaded the system updater.zip from the IP Address that was documented in the log.

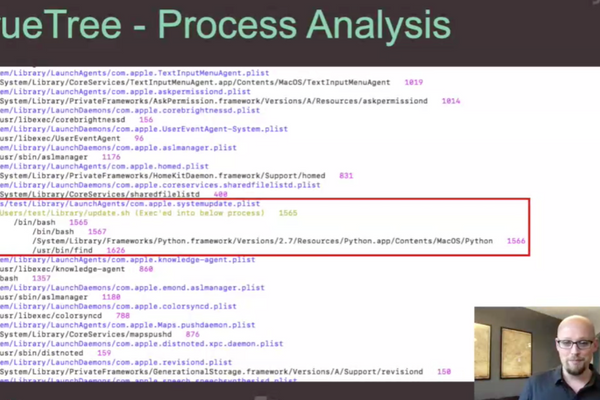

One of the best ways to catch malicious attacks is through process tree analysis. Bradley prefers to use TrueTree, written by Jaron Bradley himself! It is open-source, free and was designed to provide greater process analysis beyond what is natively available.

In the incident response script, we gained even greater insight into what occurred and the severity of the attack. Much of what is presented can be information we've already determined but it can often add additional context to your assessment.

To take this one step further, we can visit the website and look at the source code. However, if you implement this step in your process, you should do so by using a secure process like a VN or over a proxy as to not infect the host system

We can see that when a user visits the site, they are immediately redirected to a link with the SystemUpdater.zip; the zip file is automatically downloaded, followed by a seven-second hold to unzip the file and register run the custom URL scheme, and finally, the user is redirected to the CustomUrl scheme where they are prompted to open the application. We now have a full understanding of what took place at the exact moment of the security incident.

The steps we followed in this incident response, from collecting the information on the attack and analyzing the extent of its effect to watching the attack to gaining all of the data and logs needed for a comprehensive assessment, prepared and readied us for cleanup and remediation. To resolve this, we will:

- Unload the Launch Agent: launchctl unload ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.systemupdate.plist

- Delete the LaunchAgent

- Delete the malicious shell script

- Kill and delete the dropper application

In this demonstration, the incident response was fairly easy to execute because the attacker did not gain root access or drop additional malware. We investigated the alert, collected data and logs to inform our response, and remediated the security incident with Jamf Protect and Jamf Pro.

You can watch Jaron Bradley do this in real-time and greater-depth in the on demand JNUC session. We also have resources for you to learn more about Mac and security incident response like our Guide to Successful macOS Security Incident Response white paper.

But if you're ready to harness the power of Jamf, request a free trial today.

Jamf Protect

Jamf Pro

by Category:

Have market trends, Apple updates and Jamf news delivered directly to your inbox.

To learn more about how we collect, use, disclose, transfer, and store your information, please visit our Privacy Policy.